Fentanyl: The new face of the US war on the poor | Opinions

At an April 14 news conference in Washington, DC, Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) chief Anne Milgram sounded the alarm about the country’s latest appointed public enemy number one: four Mexican guys known as “Los Chapitos”, the sons of imprisoned Sinaloa cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

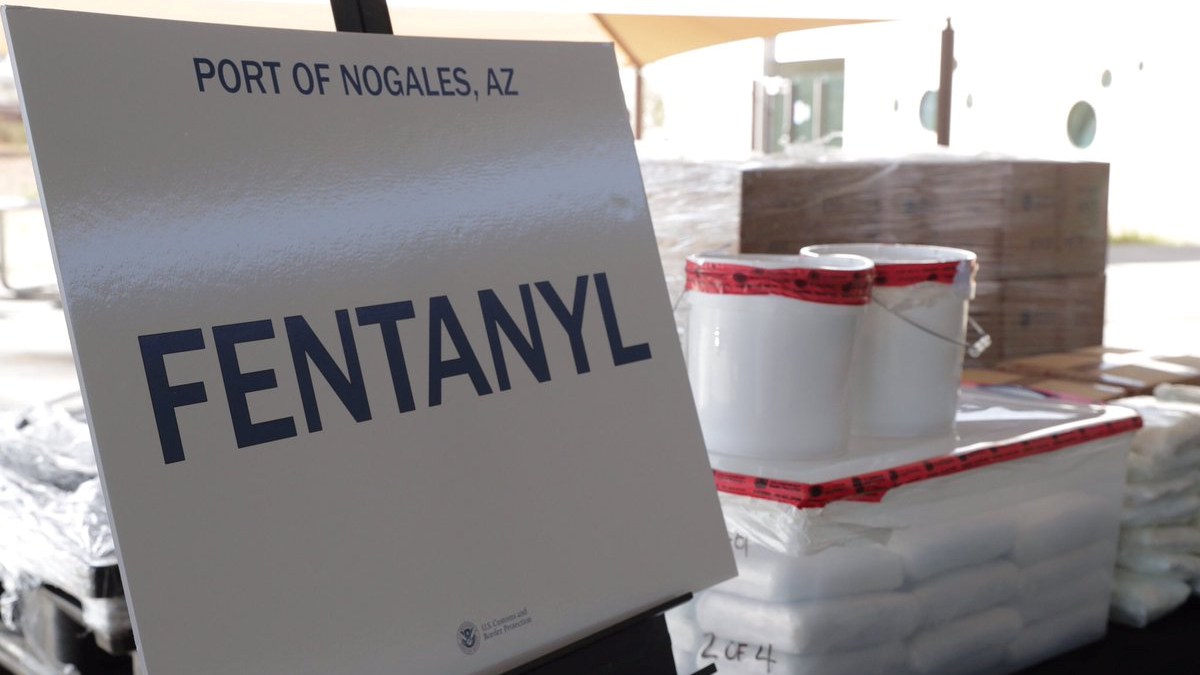

Declaring El Chapo’s offspring “responsible for the massive influx” into the United States of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, Milgram insisted: “Let me be clear that the Chapitos pioneered the manufacture and trafficking of the deadliest drug our country has ever faced.”

As if this were not news enough, the DEA chief threw in some additional alleged trivia, according to which the Chapitos had “fed their enemies alive to tigers, electrocuted them, [and] waterboarded them” – activities the likes of which the US has obviously never perpetrated against its own enemies.

There is no debating the deadliness of fentanyl, which is 50 times more powerful than heroin. Drug overdoses, the majority of them fentanyl-related, are now killing more than 100,000 people a year in the US. Entire communities have been devastated.

And yet it is curious that the Chapitos are spontaneously to blame for the whole fentanyl epidemic – although the new narrative certainly comes in handy when justifying the continuing frenzied militarisation of the US-Mexico border.

Back in 2017, a US congressional hearing on fentanyl featured testimony from Debra Houry, a director at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the national public health agency, who noted that many of those dying from fentanyl overdoses had previously been prescribed legal painkilling opioids.

As Houry explained: “People that are on prescription opioids get addicted to opioids and can then go on to overdose from heroin or fentanyl.”

So it is hardly shocking that people are dropping like flies from fentanyl given the unchecked opioid over-prescription that has epitomised the contemporary healthcare scene in the US – an arrangement that ultimately has little to do with health and lots to do with money.

Indeed, it takes a downright sick system to enable the shipment of nine million opioid pills in two years to a single pharmacy in a town with a population of 400 people, as happened in the state of West Virginia.

And while big players in the US pharmaceutical industry and pharmacy chains have recently been forced to pay symbolic financial compensation for their irresponsible practices that fuelled the crisis, there has been no actual admission of wrongdoing or any serious connecting of the deadly dots.

In other words, there has been zero reappraisal of the US’s pathological capitalist foundations – which means that silly things like human lives will never be put above corporate profit.

After all, it is easier just to blame the Chapitos.

As would be expected in any such setup, the lives of the poor matter the least. And what do you know? The fentanyl crisis has disproportionately hit poor people. A 2020 article published on the website of the National Library of Medicine found that people living under the poverty line had a higher risk of fatal opioid overdoses.

At-risk socioeconomic groups also included newly released prisoners, as well as folks with insecure housing or no health insurance. The article noted: “Economic deprivation is a risk factor for opioid overdoses in the United States and contributes to patterns of declining life expectancy that differ from most developed countries.”

How is that for American exceptionalism?

To be sure, in a country with so much pain, it makes perfect sense that there should be such a demand for painkillers – and the cheaper the better for the impoverished communities upon whose misery the capitalist superstructure is built.

Meanwhile, the more the lower socioeconomic echelons can be criminalised for their poverty and addictions, the more convenient for perpetuating the war on the poor that helps keep US society good and submissive.

The fact that US military veterans are twice as likely to die from an opioid overdose pretty well encapsulates the skewed priorities of a country that can spend trillions sowing destruction worldwide but cannot be bothered to take care of even its own warriors.

Then, of course, there is the matter of the intersection of socioeconomic and racial oppression against the backdrop of the fentanyl-dominated opioid crisis and drug overdoses in general. According to Scientific American magazine, the overall overdose death rate for Black people in the US first surpassed the death rate for white people in 2019, with the proliferation of fentanyl producing a panorama in which “Black men older than 55 who survived for decades with a heroin addiction are dying at rates four times greater than people of other races in that age group”.

The CDC reports that the overdose death rate for Black people increased by 44 percent between 2019 and 2020 alone, while the rate for Native Americans increased by 39 percent.

And in 2020, as per CDC statistics, overdose death rates for Black people in US counties with greater income inequality were more than twice as high as in counties with less income inequality.

If there was ever a lesson to learn from capitalism, it is that inequality kills. Hence the US government’s reliance on international bogeymen like the Chapitos to distract its citizens from a rather brutal reality: that the capitalist system itself is public enemy number one.

Now, US lawmakers are pushing for harsher sentencing for fentanyl possession and dealing – which is great news for the prison-industrial complex but not so much for society. One cannot help but recall the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s, when Black communities in Los Angeles were decimated by a drug influx directly occasioned by the US’s terrorisation of Nicaragua – otherwise known as the Contra war against the so-called “red menace”.

Forty years later, capitalism remains as deadly a drug as ever and a euphemism for the all-out US war on the poor – a war for which fentanyl is merely the latest face.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source