First batch of non-local doctors recruited overseas to start working in Hong Kong public hospitals this month

Dr Gladys Kwan Wai-man, a chief manager at the authority, told a press briefing on Monday that jobs had been offered to more than 100 non-local doctors, following recruitment exercises in the United Kingdom and Australia earlier this year. So far, 60 to 70 have accepted offers.

Kwan said about 10 would start working in local public hospitals this month.

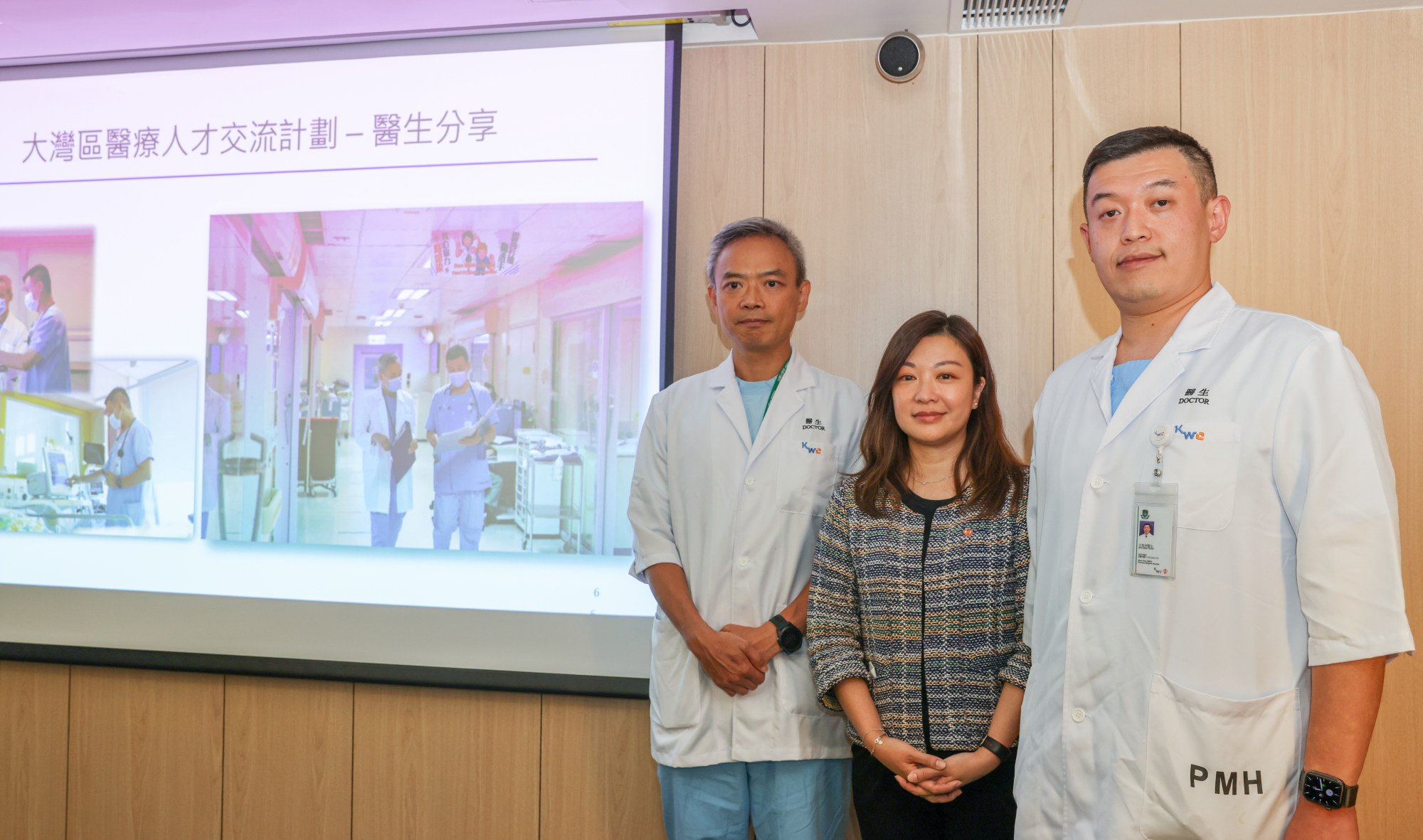

Dr Gladys Kwan, flanked by Dr Yeung Yiu-cheong (left) and Dr Kuang Yukun, says the bay area scheme is a “win-win situation”. Photo: Yik Yeung-man

The authority has launched various recruitment schemes for overseas and mainland healthcare workers this year to try to address manpower shortages in public hospitals.

Eighty-three healthcare professionals, including 10 doctors, have been working in local public hospitals under the bay area scheme which began in April this year.

“This programme gives us a very good opportunity to have this kind of collaboration or professional exchange at a clinical level, so that we know the expertise there and in return they also know how the system works in Hong Kong,” Kwan said on Monday.

“This is a win-win situation.”

She added: “We made use of this expertise as well as the manpower to support our public system at a moment when we are facing quite a significant shortage of manpower.”

Hong Kong’s makeshift Covid-19 hospital will add services to help public sector

Kwan said the programme, which also involved nurses and Chinese medicine practitioners, would be regularised in the future. But details such as the number of participants and specialties involved, and modes of exchange, were still under discussion between Hong Kong and the mainland, she said.

Dr Kuang Yukun, an expert in respiratory medicine from the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, is one of three mainland doctors working in Princess Margaret Hospital under the programme.

Kuang, who worked in the hospital’s department of medicine and geriatrics, was involved in ward rounds, outpatient clinics and other clinical inspections, like local doctors.

He said it took him some time to adapt to the different language environment in Hong Kong.

“On the mainland, we use Chinese for communications and medical records,” Kuang said. “But here in Hong Kong, many records and communications are in English. While my English level is not bad, it also took me some time to get adapted to this.”

Change rules so more Hong Kong doctors can work on mainland: ex-health secretary

But he said language differences did not affect how he handled patients.

“On medical procedures, no matter if it is Chinese, Japanese or English, the principle is the same,” he said.

Kuang, who joined a mainland medical support team in Hong Kong last year during the fifth Covid-19 wave, said the city’s healthcare system provided good continuity of care for patients.

He said patients usually received follow-up rehabilitation after their acute conditions had been treated, and that doctors needed to liaise with nurses or units about services – steps he had not carried out before on the mainland.

Kuang said the clinical management computer system used by all public hospitals also allowed better communication between institutions in case of patient transfer.

He noted that the quality of Hong Kong doctors, no matter if they worked in acute or rehabilitation hospitals, was similar. But there was a difference in professional levels among doctors at different hospitals on the mainland, he said.

Hong Kong minister raises concerns as public sector doctors quit after specialising

Upon returning to the mainland, Kuang said, he hoped to bring the city’s healthcare practice of clearly defined work roles between doctors, nurses and administrative support staff to his institution in Guangzhou.

He also envisioned raising the level of mainland junior doctors, describing younger counterparts in Hong Kong as possessing rather “thorough and in-depth” medical knowledge.

Dr Yeung Yiu-cheong, the department’s deputy chief of service, said mainland doctors could work independently after being supervised by local colleagues for the first one to two months. But they had to be supervised by local specialists when conducting invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy.

But he said the extra supervision would not affect the efficiency of medical services.

“After they adapt to the work, they can help us a lot with manpower,” he said.

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source