Large areas of Missouri and Kansas lack primary care doctors. How can medical schools help? | KCUR

In the simulation center at Kansas City University, hundreds of prospective doctors work on their physician-patient interactions.

The state-of-the-art lab offers students a chance to prepare for different situations they’ll face in a medical practice. In one room, students care for a nauseous patient, working as a team to diagnose and treat them. After, they’ll debrief with professors about the process and outcome.

More than 1,500 doctors come to Kansas City University each year, and hundreds more go to nearby medical schools at the University of Kansas and the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

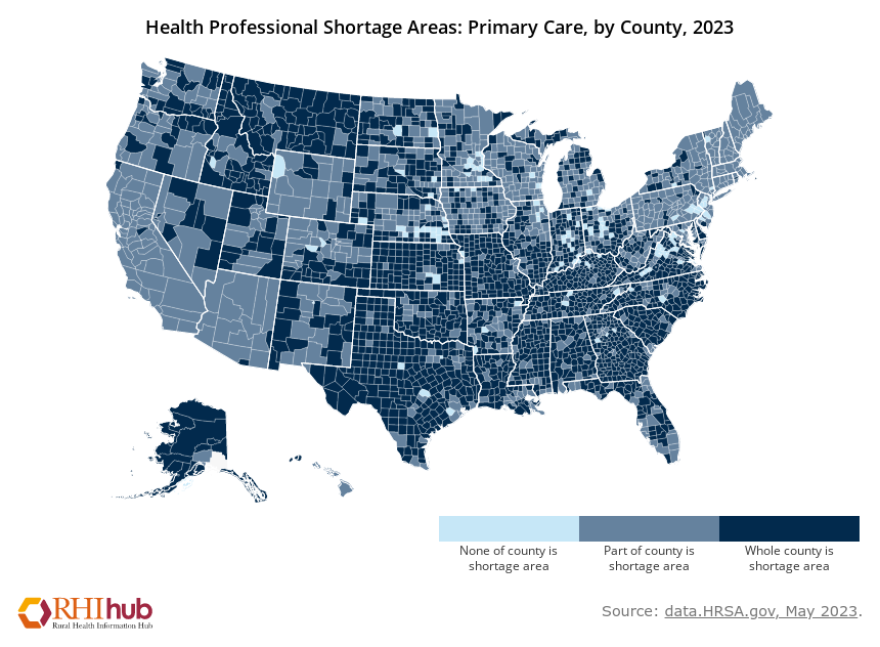

While many new students interested in health care are coming into Kansas and Missouri through these programs, as much as 80% of Missouri and about 50% of Kansas lacks a primary care provider

“We know that about 20% of the US population lives in rural areas, but only about 11% of the physician population is actually in those areas,” said Russell Kohl, a member of the American Academy of Family Physicians board of directors who lives in Stilwell, Kansas. “So, two-thirds of all rural areas in the U.S. have a primary care shortage.”

There are shortages in the metro area as well, where Wyandotte County has half as many primary care providers as Johnson County. What those shortages look like may differ: a rural county without a provider might require folks to drive two hours, whereas an urban shortage might mean higher caseloads for doctors and longer wait times for patients.

But in either case, the consequences falls heavily on patients.

Demand for health care in Wyandotte County has increased over the past decade as its population — and Johnson County’s — have continued to grow. To try to keep up, medical schools are creating new programs aimed toward at the very least encouraging interest in work in underserved communities.

Train-and-retain

In the simulation center at Kansas City University, students prepare for jobs and scenarios down the line. The university is hoping to guide some of these students into primary care specialties, in hopes they may practice in an underserved area.

KCU, located in Kansas City, Kansas, enrolls about 1,600 students each year. Most study in Kansas City, but about one-third learn at the university’s Joplin campus.

KCU executive dean Josh Cox said the Joplin campus is one example of a train-and-retain mentality the school employs to encourage students to stay in the community.

“If they take their medical training there, they’re more likely to practice clinical medicine after all of their training is accomplished,” Cox said. “The same thing goes here in our Kansas City campus.”

KCU partners with federally qualified health centers in Kansas City, which serve uninsured and low-income patients, to give students hands-on experience so they’ll know the community better and might want to stay after they’ve finished their training.

Currently, between 50% and 60% of KCU graduates per academic year pursue specialties in the primary care field. A 2021 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association ranked KCU ninth in the nation in getting doctors into primary care. It has also taught more primary care providers practicing in Missouri than any other medical school.

In Kansas, that title belongs to the KU Medical Center, where a similar train-and-retain idea is being applied to help fill gaps across the state. For example, required rotations for fourth-year students send each prospective doctor to a rural location.

Efforts to medical school efforts are going to likely to pay dividends, but any attempt at patching the pipeline is going to take some time and patience as most counties across Kansas and Missouri are in need of doctors.

Leveraging residencies

Residency programs are one of the most critical tools for addressing shortages and healthcare deserts in medical school.

Residencies usually span from three to seven years depending on the medical specialty, with primary care usually on the shorter side. During these years, graduates work in hospitals, clinics or medical offices to diagnose, control and treat medical issues.

Residency applicants submit materials and go through an interview process, and then, on what is known as “Match Day,” the National Resident Matching Program releases results to applicants, pairing applicants into residency and fellowship opportunities based on a mathematical algorithm.

While a university ultimately has no say in what county or even state a student will end up in, they can partner with rural and underserved community providers to create residency spots and incentivize students to seek these avenues out.

At KU Med, a partnership with the Community Health Center of Southeast Kansas that launched in 2022 is for the first time this year allowing two family medicine residents to work in Pittsburg. After one year spent in residency at KU Medical Center in Kansas City, they will spend the next two years at the health center, a federally qualified location for medically underserved people.

Southeast Kansas has the highest rate of chronic disease in the state, according to the KansasHealthMatters community dashboard.

“Research shows that where physicians train in their residency is one of the highest indicators of where they will practice,” said Jennifer Bacani McKenney, M.D., associate dean for rural health education at KU Medical Center. “If we want people to practice in rural areas, we need to train them in rural areas.”

The Kansas Medical Student Loan Program goes even further by helping students cover the cost of school in exchange for agreements to practice medicine in an underserved Kansas community after their residency. Currently, there are 118 providers supported by the program, 29 of them in Wyandotte County.

Associate Dean of Student Affairs Mark Meyer says 60 of 105 Kansas Counties gained at least one doctor through the program in the last decade.

“It is probably one of the longest-standing pathway programs of taking a student from day one of medical school, placing them in an underserved community and getting them to stick there,” Meyer said.

Among all medical schools, public or private, KU Med ranks among the best at sending graduates to practice rural areas and are better than most when it comes to graduates in underserved areas.

In addition, the percentage of graduates ending up in primary care residents has increased from just under 30% between 2008 and 2012 to 45% of graduates from the Kansas City campus and 53% from the Wichita campus.

Patching the pipeline

Carlos Moreno

/

KCUR 89.3

KU Medical Center in Kansas City.

While schools are trying to get students to areas in need of a primary care doctor, Meyer says the pipeline remains leaky, especially in medical education, where it takes a long time before you have gainful employment. Challenges at all stages can lead to students dropping out.

Kohl said the medical schools’ efforts are going to pay dividends, but any attempt at patching the pipeline is going to take some time and patience.

“People coming into medicine have to be patient,” Kohl said. “We’re sometimes seven to 11 years down the road to being able to see the impact of the actions.”

At a minimum, primary care physicians are looking at a seven-year path to gainful employment once they enter medical school. One main reason students drop out is the exorbitant costs of medical school — where the average student leaves with about $200,000 in debt — but an academic setback or personal issues can easily cause a student to slip through the cracks.

Kohl, of the AAFP, thinks policymakers should closely examine how graduate medical education is funded, and put a greater emphasis on training primary care physicians.

At the state level, Kohl said loan repayment programs like the Kansas program and tax credit incentives can work well. He also said legislators should consider stipulations on funding requiring a certain amount of graduates to go into primary care or practice in the state.

And at a local level, especially in rural areas where doctors might be swamped, Kohl simply asked for grace.

“If I was running late, it wasn’t because I didn’t care about you. It was because I just had to diagnose somebody with cancer. And as their eyes teared up and I had to hold their hand to talk to them a few minutes, I needed to be a real doctor with them,” Kohl said. “It is not a system that is designed to offend you, it’s the time that somebody needs to get the care that they need, and they want to do the same thing with you.”

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source