Selling Hikma Pharmaceuticals After A 40% Share Price Gain In 7 Months (undefined:HKMPF)

Maxiphoto

Hikma Pharmaceuticals (OTCPK:HKMPF, OTCPK:HKMPY) is a FTSE 250 generic drug manufacturer that was founded in the Middle East in 1978.

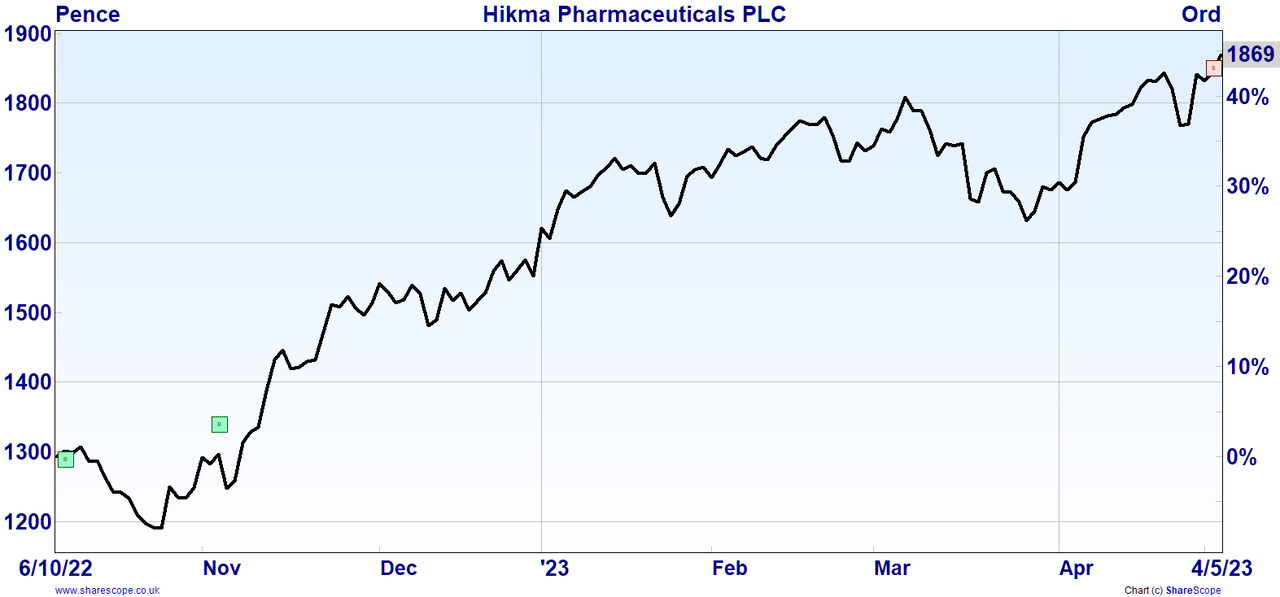

The company has many attractive features, including a long track record of progressive dividend growth, so I added it to my dividend portfolio in October 2022 at an average share price of £13.20.

Since then, Hikma’s share price has gone up by 40%, to £18.51. Obviously I’m happy with that, but the company’s valuation and dividend yield are no longer as attractive as they once were, so I have decided to sell all of my Hikma shares and reinvest the proceeds elsewhere within the portfolio.

Although I’m selling, I would happily reinvest in Hikma at the right price, so in the rest of this post I’ll explain why I like Hikma, what I think its fair value is and what share price I would reinvest at.

You can also download my original purchase review and subsequent sale review in PDF format (both extracted from my monthly investment newsletter):

- Hikma Pharmaceuticals – Oct 2022 Purchase Review (PDF)

- Hikma Pharmaceuticals – May 2023 Sale Review (PDF)

Also, if you’re not familiar with how I analyse companies, I always follow the same dividend investing checklist, which includes a number of questions that examine the quality, defensiveness and value of a business.

Introduction

Hikma was founded in 1978 by Samih Darwazah, who was mid-way through a successful career in the pharmaceutical industry. Darwazah’s work had taken him all over the world, but at 46 he wanted to return to the Middle East to put down roots for his family. He also wanted to give something back to the region by helping it develop a thriving pharmaceutical industry.

He decided to build a pharmaceutical manufacturing business, making generic medicines (those no longer protected by patents) as well as medicines manufactured under licence from patent-holders.

The company’s first facility was built in Jordan to serve the local market and, since then, Hikma has grown to become a leading manufacturer of generic and in-licence medicines, with operations in the Middle East, the US and Europe.

Here’s a snapshot of Hikma’s key statistics, as they were in October 2022 (when the share price was £13.20):

| Margin of Safety90% (min 66%) | Dividend Yield3.6% (min 2%) | Growth Rate9.4% (min 2%) | Growth Quality88% (min 66%) | Return on Capital12% (min 10%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Return on Sales16% (min 5%) | Debt Ratio2.9 (max 5.0) | Pension Ratio0 (max 10) | Capex Ratio54% (max 100%) | Acquisition Ratio68% (max 100%) |

Click to enlarge

Quality: Is Hikma a quality company?

Q1. Does it have a focused core business?

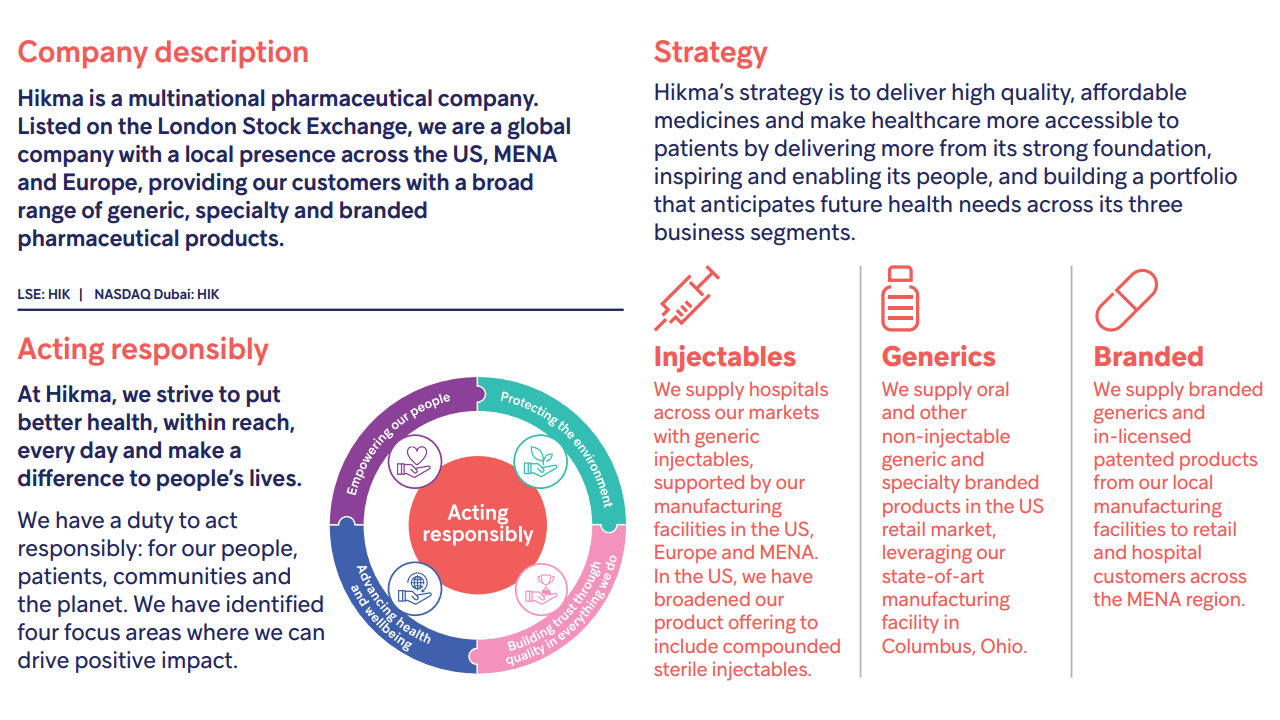

YES: Hikma manufactures, sells and distributes medicines and other pharmaceutical products, primarily in the US, the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) and Europe. At a high level, Hikma’s products can be categorised as:

In-licence: These medicines are protected by patents and can only be manufactured by the originator (companies like GSK (GSK) that develop new medicines) or under licence from the originator.

Branded: These medicines are no longer protected by patents (patents typically expire after 20 years), so they’re sold under a trademarked brand name in an attempt to maintain higher prices and higher profit margins. An example would be Nurofen, which is a branded version of the generic medicine Ibuprofen. Hikma manufactures branded products under licence from brand owners and it also has brands of its own.

Generics: These medicines are out of patent and are sold without a brand name. To continue the Nurofen example from above, this would be Ibuprofen sold simply as “Ibuprofen”. With unbranded generics, customers usually care more about price than anything else.

Hikma manufactures all of the above products across three divisions:

Injectables (46% of core revenues): Hikma produces sterile injectable medicines for hospitals across the US, MENA and Europe, from manufacturing facilities in each of those regions. The US is the largest market in the world, where Hikma is the number two supplier behind Pfizer (PFE).

This is the largest and most profitable division, with operating margins averaging 36% over the last ten years. These high margins are possible because injectables have higher technological and regulatory barriers to entry, mainly because injectable medicines are more dangerous than non-injectables, such as tablets. They’re more dangerous because they’re injected directly into the body, sidestepping the powerful anti-infection capabilities of the digestive system.

Generics (27% of core revenues): The generics division manufactures non-injectable generic medicines in the US for the US market, where Hikma is a top-ten supplier.

These medicines are pure commodities, because aspirin from one manufacturer is chemically and functionally identical to aspirin from another manufacturer. This is a problem because it makes non-injectable unbranded generics brutally price competitive, as there’s little else to compete on (although a reputation for quality and reliability can sometimes make a difference).

However, from a societal point of view this is fantastic, because generic drug manufacturers like Hikma continuously drive prices down, making out-of-patent medicines more affordable for more of the world’s population.

Branded (28% of core revenues): This is Hikma’s traditional core business. It mostly sells branded generic and in-licence patented medicines in the MENA region, where Hikma is the third-largest supplier behind well-known multinationals Novartis (NVS) and Pfizer.

MENA is different from other markets in several ways:

- People in that region tend to prefer branded medicines because they don’t trust unbranded generics.

- Many MENA governments insist on local production as a way of boosting the local economy, so instead of having one or two huge and efficient manufacturing facilities serving the entire region, Hikma has 23 facilities dotted across multiple countries.

- Unlike the US market, where hospitals and other customers form alliances to increase their ability to dictate prices, the MENA market is far more fragmented. To thrive in this fragmented market, Hikma has more than 2,000 salespeople in the MENA region engaging with doctors and pharmacists.

Q.2. Has it had the same core business for over a decade?

YES: Hikma has been a pharmaceutical manufacturer since 1978, but the company is split into three divisions and each has a somewhat different history.

The Branded division began when Hikma opened its first manufacturing plant in Jordan in 1978. Initially, its products were only sold in Jordan, but within a few years it was exporting generic, branded and in-licence medicines across the MENA region and beyond, as it still does today.

The Generics division began in 1991 when Samih Darwazah sent his son, Said, to find a US pharmaceutical company to acquire. They eventually purchased West-Ward Pharmaceuticals for $2.5 million, which was a bargain price because the acquired facility was poorly run and at risk of losing its authorisation from the US FDA. Although it took several years, the West-Ward facility was successfully turned around and for many years it formed the centre of Hikma’s US operations.

The Injectables division also began in the early 1990s when Samih Darwazah decided to expand into Europe by entering the attractive and underserved Portuguese market. He was unable to find a suitable acquisition target, so he had a new facility built from scratch. This meant the facilities could be built to Darwazah’s exacting standards, so Hikma pulled out all the stops and built a world-class injectables facility that would have the capacity and regulatory approvals to export all over the world.

Each division is now multiple decades old and each has stuck firmly to its core business of manufacturing high-quality generic or in-licence medicines.

Q.3. Has it had broadly the same goal and strategy for more than a decade?

YES: Samih Darwazah had a comfortable life when he founded Hikma at the age of 46, so he had no obvious need to sink his life savings into building a pharmaceutical manufacturing facility in the Middle East. He did this for three reasons:

- He was clearly a man of great talent and ambition and his pharmaceutical career was perhaps not sufficiently stretching

- He wanted to make medicines more affordable and available across the MENA region

- He wanted to improve the economies of the Middle East by helping the region build an industry that would require many highly educated workers

Much has changed since 1978, but Hikma’s primary goal of creating more high-quality medicines and more high-quality jobs remains unchanged.

The company has pursued these goals through a strategy that has remained broadly unchanged from the beginning, and it flows logically from the founder’s original dream.

Grow by maintaining a reputation for quality

Darwazah wanted to build a company that would lift up the Middle East, requiring highly educated engineers, chemists, pharmacists, managers, salespeople and so on. He wanted to pay them well so they would be able to spend that money to further boost the local economy. He wanted to build a world-class Arab business that would instill a sense of pride in the Arab people.

Paying people well doesn’t fit with the model of being a low-cost generics manufacturer, so Darwazah wanted Hikma to compete on quality, not price. In fact, in the early years, Hikma’s logo showed that Quality was literally the foundation of the business.

This is why Hikma did whatever it took (and it took 14 long years) to become the first Middle Eastern pharmaceutical company to have its manufacturing facility approved by the US FDA. This clearly differentiated Hikma from its MENA peers in terms of its reputation for quality, and it also gave Hikma a cost-competitive facility that could export to the US.

An obsession with quality is also why Hikma focuses on injectable, branded and in-licence medicines. Injectables require extremely high-quality sterile facilities, while branded and in-licence medicines need to be high quality because they’re sold at a higher price than unbranded generics.

Grow by expanding into new products

Hikma started in 1978 with one product and expanded from there. Each product takes time to launch because Hikma has to develop its particular formulation, dosing and so on, and then everything has to be tested and approved by regulators. In some sense, the last 40 years have been a continuous process of adding new medicines to Hikma’s ever-broadening range.

For example, in 2021, Hikma launched 15 new injectables in the US and 34 across Europe, and it launched 40 new branded products in MENA. And as if that wasn’t enough, Hikma also launched a new sterile compounding business.

Grow by expanding into differentiated products

Hikma’s focus on quality has always steered it towards differentiated products that demand higher quality manufacturing, whether for safety, technical or marketing reasons.

The Injectables division is a good example, where quality is necessary for safety reasons. The Injectables division has grown to become Hikma’s largest and most profitable division and it’s likely to be an increasingly important engine for future growth. To support the expansion of this division, Hikma is currently spending around $30-40 million each year to upgrade and expand its already class-leading injectables facilities.

Another example of Hikma’s focus on differentiated products is its generic version of GSK’s Advair Diskus, an inhaler that is used to treat asthma. Advair Diskus went off-patent in 2010, but it is incredibly difficult to manufacture, so generic versions have been slow to appear (this is partly by design as it allows GSK to keep prices high even after the patent has expired). However, Hikma has been working on its version for years and it was finally launched in 2021, becoming only the second generic Advair Diskus in the world.

As an early entrant with this product, competition is low, so prices and profit margins should remain high, at least for a while. This is exactly why Hikma typically invests around 6-7% of revenues into R&D and is always looking to develop and manufacture medicines that other generic manufacturers cannot.

Grow by expanding internationally

Hikma was born in Jordan but Jordan is a relatively small market, so Darwazah knew that Hikma would expand internationally as soon as it became feasible, and this continues today. The Injectables division recently entered the Canadian market through an acquisition and Hikma is expanding into France, Spain and other European countries in order to win more pan-European supply contracts.

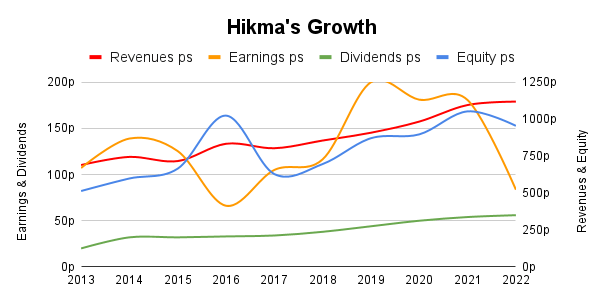

Q.4. Has it produced consistent and sustainable growth?

YES and NO: Measured across shareholder equity, revenues and dividends, Hikma achieved a Growth Rate of almost 8% over the last decade and that exceeds my rule of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its Growth Rate is above 2%

Data source: SharePad

Looking back to the previous decade, growth was even steadier and much faster at about 20% per year. That sounds good, but I’m not a fan of rapid growth because it often causes problems. It’s a bit like building a house too quickly; if the foundations aren’t sturdy or if the walls aren’t straight, the house could collapse when it faces its first storm.

The very rapid growth before 2013 wasn’t sustainable because it was fuelled by debt and acquisitions, so from a sustainability point of view, I’m happy to see Hikma’s growth slowing to a more sensible 8% per year.

I should also point out that the chart above uses adjusted earnings in 2017 rather than reported earnings, because the reported earnings were strongly negative after Hikma wrote down the value of an acquisition by $1 billion. That write-down doesn’t reflect the operational performance of the business, which is why I’ve excluded it here, but it was a major blunder and I’ll address it in a later question.

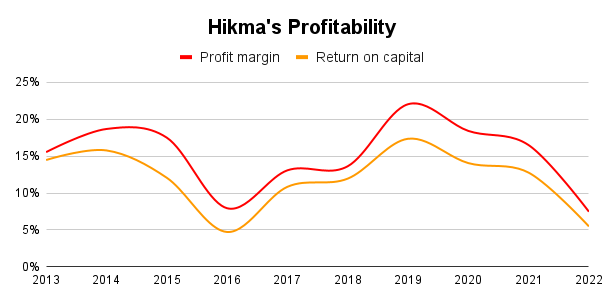

Q.5. Has it earned consistently good returns?

YES: Over the last ten years, Hikma produced an average return on capital of 12%, which is above average and above my minimum threshold.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its ten-year average return on capital is above 10%

As for profit margins, these averaged almost 16% over the last decade, well above my threshold.

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if its ten-year average profit margin is above 5%

These results also ignore the reported loss in 2017, because that related specifically to the price paid for an acquisition rather than the company’s operational performance, and operational performance is what I’m really interested in at this stage.

Q.6. Has most of its growth been organic?

NO: Although Hikma has produced a lot of organic growth over the years, acquisitions have always been a key part of its growth strategy.

Typically, Hikma will expand into a new country or market segment by acquiring an existing player. It then brings the acquired company’s operations up to Hikma’s high standards and expands organically from there, adding new production lines and products.

This is an entirely reasonable strategy, but what matters is the scale of these acquisitions. Small bolt-on acquisitions can be easily digested by most companies, while large acquisitions frequently cause indigestion.

In Hikma’s case, during the 2002 to 2011 period, it earned a total of $540 million, but spent over $600 million on acquisitions. This almost breaks one of my rules of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Don’t invest in a company if it spent more on acquisitions than it made in total profit over the last ten years

This does break my rule in terms of the scale of the acquisitions, but I’m talking about the 2002-2011 period, which is more than ten years ago. However, it does show that acquisitions were a significant part of Hikma’s growth story and acquisitions can cause problems long after the deal has been signed.

Looking at the most recent ten-year period, Hikma spent a total of $2 billion on acquisitions and earned a total of $2.9 billion, so the ratio of acquisitions to earnings was 69%, which is still high but acceptable.

On the face of it then, Hikma no longer seems to be overly acquisitive, but that ignores the fact that almost all of that $2 billion was spent on a single acquisition, and in my experience, as the size of an acquisition grows, the risk of damage increases exponentially (a bit like the Richter Scale for earthquakes).

In this case, Hikma acquired Roxane Laboratories for $1.6 billion in 2015/2016. At the time, Hikma was earning about $250 million per year, so this acquisition cost almost seven-times Hikma’s average annual earnings. If this acquisition was an earthquake, it would have a magnitude of seven on the Richter Scale and the potential to cause “serious damage”.

The good news is that buying Roxane made a lot of sense because it had world-class facilities in the US and a large portfolio and pipeline of products. And, critically, those products were complex and had multiple layers of differentiation, which are important for maintaining higher profit margins.

The bad news is that the mid-2010s was a period of brutal price competition and by the end of 2017, just a few months after the acquisition, it became clear that Roxane wasn’t going to produce anything like the profits Hikma had expected.

In its 2017 annual report, Hikma wrote down the value of Roxane by $1 billion, which was 63% of the purchase price. Clearly, Hikma’s management had paid far too much for Roxane and a mistake of this magnitude was unacceptable.

Said Darwazah (the founder’s son) was CEO and Chairman at the time. Any normal CEO would have been kicked out immediately, but Said owns 6% of the company and the Darwazah family owns another 27%, so they can pretty much do what they like. But credit where credit is due, Said stood aside and hired an external CEO to take Hikma forward.

Given the scale of this mistake, why did I not immediately rule out an investment in Hikma?

The answer is that Hikma’s management seem to have learned their lesson. They allowed their confidence to get ahead of their competence and they paid far too much for Roxane, but in the seven years since the Roxane acquisition, Hikma has become notably less acquisitive.

More specifically, the total spent on acquisitions since 2016 comes to little more than $500 million, while earnings have totalled more than $2 billion, so the acquisition to earnings ratio is around 25% and that is much more prudent.

Q.7. Does it gain an advantage from network effects?

NO: Network effects occur when the usefulness of a product or service depends upon the number of customers or users, as is the case with two-sided marketplaces like Rightmove or social networks like Facebook. This doesn’t apply to medicines so Hikma doesn’t have network effects.

Q.8. Does it gain an advantage from valuable, rare and hard to replicate assets?

YES: Hikma’s most important asset was its founder, who was clearly a genius when it came to building a business. However, a genius founder only becomes a durable competitive advantage if the founder’s methods become deeply ingrained in the company’s culture. If that happens, the founder’s genius can endure long after they’ve gone.

In Hikma’s case, I think this has been achieved. That’s partly because the founder was directly involved in the business between 1978 and 2014. It’s also because his son ran the business for many years and is still Chairman today. It’s also because the founder’s philosophy was very employee-centric, so employees are more than happy to maintain the founder’s culture.

As I mentioned earlier, Samih Darwazah didn’t create Hikma to get rich. He created the company to benefit the people of the Middle East with high-quality medicines and high-quality jobs, so the business exists for people first and profit second.

You can see this in many of Darwazah’s guiding principles. For example:

- Employees will be treated with equal respect

- Hiring will be meritocratic with no preference for men or women

- Hikma will pay for whatever level of education and training is necessary

- Employees will be encouraged to give feedback and management (including the CEO) will maintain an “open door” policy

- Employees will have access to free hot food at lunchtime

I am very much a fan of this type of employee-first approach, because “people who like what they do, do it better” (a phrase borrowed from the founder of one of my holdings, Admiral Insurance (OTCPK:AMIGF, OTCPK:AMIGY)). Happy employees also tend to stick around longer, which reduces recruitment costs and, more importantly, helps retain the best and most experienced people.

In my experience, very few companies can develop and maintain a truly employee-centric approach, which is why it can be a powerful and enduring competitive advantage.

Q.9. Does it gain an advantage from core market leadership?

YES and NO: In the Branded division, Hikma does have some scale and market leadership advantages. It’s the largest local player across the MENA region and that (combined with its reputation for quality and reliability) makes it the manufacturing and distribution partner of choice for outsiders.

For example, in an increasing number of MENA countries, governments have a strong preference for medicines to be manufactured locally rather than imported. Hikma already has 23 plants spread across many different MENA countries, so if a Japanese pharmaceutical giant wants to sell a new medicine in the MENA region, it’s much easier to get Hikma to do the manufacturing and selling, rather than trying to set up its own local facilities.

Also, given the MENA region’s ongoing instability, the fact that Hikma’s people are locals is an advantage. After all, they’re not going to jump on a plane back to the US or Europe whenever the next war or military coup takes place.

In the Generics division, scale is extremely important because it allows Hikma to have a diversified (and therefore lower-risk) portfolio of products while still having good economies of scale. This is largely why Hikma purchased Roxane. It moved Hikma from 20th place in the US into the top ten, but Hikma’s Generics division is still much smaller than the market leader.

The injectables division also has enough scale to manufacture a diverse range of products, which is a key defence against price erosion. The good news is that Hikma is the number two US injectables manufacturer by volume, so in its largest and most profitable division, scale is more of an advantage than a disadvantage.

Q.10. Does it gain an advantage from switching costs?

NO: There are some costs for customers who want to switch to another supplier, at least in the US and Europe. In those regions, customers are often very large (e.g. wholesalers, governments or buying consortia), so they and Hikma usually sign large multi-year supply agreements that neither party can easily switch out of.

However, I wouldn’t classify this as a meaningful barrier to customer exit because the multi-million-dollar benefits of switching to a cheaper supplier can easily outweigh related costs in terms of time and effort.

Defensiveness: Is Hikma a defensive company?

D.1. Are supply, demand and pricing stable in its core market?

YES and NO: Demand for medicines is defensive because people get sick regardless of what the economy is doing. Supply is also defensive as long as manufacturers can get hold of the necessary raw materials (known as active pharmaceutical ingredients or APIs). Pricing, on the other hand, is far less stable because prices for generic medicines are in constant decline, but this can be offset in several ways.

The first line of defence against price erosion is to manufacture differentiated products. These might be products that are particularly hard to make, such as injectables, or they could be branded products that are protected by trademarks (such as Hikma’s Kloxxado nasal spray).

The second line of defence against price erosion is to not rely heavily on any one product or type of product, so Hikma sells almost 700 medicines across generics, injectables, branded and in-licence.

Hikma’s third line of defence against price erosion is to invest 6-7% of revenues into R&D each year to maintain a pipeline of new medicines. A good example is Hikma’s generic Advair Diskus, which took years of development, is one of only two versions currently authorised and which should be able to generate decent profits for at least several years.

So, although price erosion and price instability has caused Hikma’s earnings to be somewhat volatile over the years, I would still classify it as a defensive business.

D.2. Is it largely unaffected by commodity prices?

YES: Although chemicals, plastics and other commodities are used in the production of medicines, they don’t have a significant impact on Hikma’s profitability.

D.3. Is its core market expected to grow over the next few decades?

YES: The global pharmaceutical market is expected to grow for the foreseeable future, driven by an increase in the global population’s size, age and wealth. Taking each of Hikma’s divisions in turn:

Injectables – The global market for generic sterile injectables is expected to grow at or above 10% per year for the next decade.

Generics – The generic non-injectable market is expected to grow at close to 10% per year.

Branded – This division sells mostly into the MENA region where rapid increases in the population’s size, age and wealth are likely to drive robust long-term growth.

Overall then, it seems that global pharmaceutical sales are very likely to grow ahead of the global economy for decades to come.

D.4. Is its core market likely to avoid disruption in the next decade?

YES: The pharmaceutical industry is, understandably, highly regulated, with everything from medicines to manufacturing facilities and even prices being regulated. If a key area of regulation changed abruptly, that could be a big problem for Hikma. This risk is somewhat offset by Hikma’s geographic diversity, with just 60% of revenues coming from the US and even less from other countries, but to be honest, I don’t see regulatory disruption as a significant risk.

A more serious source of risk comes from the commoditised nature of generic medicines, which leads to aggressive competition and price erosion. In recent years, competition from Indian manufacturers has made non-injectable generics a very difficult market to operate in. To offset these disruptive pricing pressures, Hikma’s Generics division is repositioning its product portfolio towards specialty generics, which are so complex that few generic manufacturers have the ability to produce them.

D.5. Is it free from significant customer or supplier risk?

NO: Unfortunately, Hikma is exposed to a fair amount of customer concentration risk because its medicines are often purchased by large government agencies, wholesalers or buying consortia.

For example, in the US, 90% of generics are purchased by four very large buying consortia, so these organisations have enormous bargaining power (which is why they exist).

In Hikma’s case, 38% of its revenues come from three key wholesalers. This means that one of those wholesalers must make up more than 10% of Hikma’s revenues, and that breaks one of my rules of thumb:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a company if no single customer generates more than 10% of its revenues

Hikma’s management is well-aware of this risk and it’s one of the reasons why the company is looking to expand outside the US, even though the US is the world’s largest pharmaceutical market. For example, Hikma recently expanded into Canada and it’s in the process of adding new capacity for the European market.

Although Hikma breaks this rule of thumb, I am willing to accept this risk because the degree of customer concentration is probably only slightly above my 10% threshold. Also, Hikma is expanding outside the US into markets that have smaller customers, so hopefully the level of customer concentration will fall over time.

D.6. Is it free from significant product or patent risk?

YES: Hikma manufactures more than 700 products and there doesn’t seem to be any meaningful degree of product concentration.

The highest degree of concentration is in the Injectables division, where the top ten products make up 42% of revenues. However, Injectables only makes up 41% of group revenues, so I doubt that any one product makes up more than 10% of total revenues.

As for patent risk, Hikma is a generics manufacturer, so it doesn’t rely heavily on patents.

D.7. Does it have prudent financial liabilities?

YES: Hikma has a history of taking on large amounts of debt to fund acquisitions, but following the Roxane disaster, all that has changed.

Today, Hikma has debts (borrowings and lease liabilities) totalling $1.3 billion compared to ten-year average earnings of $0.3 billion. That gives the company a debt to average earnings ratio of 4.3, which is high but below my threshold:

- Rule of thumb: Only invest in a defensive company if it the ratio of debt to average earnings is below five

Value: Is Hikma good value at its current share price?

I’m a dividend investor, so I value companies based on the present value of all their future dividends. This means that in order to value a company, I have to come up with a realistic but conservative estimate of its future dividends.

V.1. Is it free of current problems that could seriously impact future dividends?

YES: I can’t see any current problems that are obvious threats to Hikma’s longer-term success. It doesn’t have excessive debts, the current downturn doesn’t really affect demand for medicines and the business is firing, more or less, on all cylinders.

V.2. Is dividend growth very likely over the next ten years and beyond?

YES: Hikma operates in markets that are expected to grow faster than the global economy over the coming decades, it has a lot of room for market share growth and there are many countries where it generates no sales at all.

Taking all of that into account, I see no obvious reason why Hikma can’t continue growing long into the future, as long as it maintains its reputation for quality and reliability, underpinned by its focus on quality people, quality facilities and differentiated products.

V.3. What is a realistic and conservative estimate of fair value?

To estimate fair value, we need to estimate Hikma’s future dividends and to do that, we need to make certain assumptions about how much the company will earn, how much of those earnings it will retain to drive growth and how much it will pay out as dividends. There are two complementary ways to do this: Top-down and bottom-up.

The top-down approach looks at external factors, such as how many stores the company could open each year or how much the company could increase its market share.

The bottom-up approach looks at internal factors, primarily how much the company earns on its equity and debt capital.

For some companies, external factors are the main growth constraints while in other companies, those limits are driven by internal factors.

In Hikma’s case, I think the external and internal factors are broadly in balance. I think the company’s 8% growth rate over the last decade probably represents a reasonable upper limit on the amount of growth that is available in the market and the amount of growth that Hikma can sustain without taking on lots of debt and without causing stress fractures within the business.

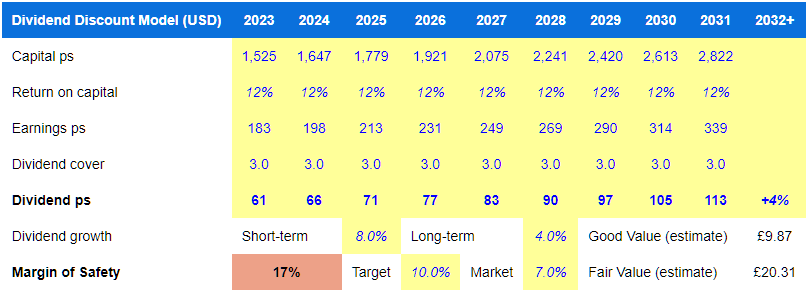

My model for Hikma is therefore quite simple and is based on the following assumptions:

- Return on capital stays at a historically average 12%

- Dividend cover stays at a historically average 3.0

- This provides sufficient retained earnings to fund a growth rate of 8% per year, in line with Hikma’s growth over the last decade

- Hikma’s long-term growth falls to 4% after 2032 as the company matures. This is slightly above the expected 3% growth rate of the global economy because spending on medicines is expected to grow ahead of the overall economy as the world’s population becomes larger, older and wealthier.

Plugging those assumptions into my Company Review Spreadsheet produces the following model:

If you haven’t seen one of these dividend models before, here’s a quick explanation of the main outputs:

- Good Value: This is my target buy price. It’s the price at which the expected return from the investment is equal to my target return of 10% per year.

- Fair Value: This is my target sell price. It’s the price at which the expected return from the investment is equal to the UK stock market’s average return of 7%.

- Margin of Safety: This tells you exactly where the share price is between Fair Value (Margin of Safety = 0%) and Good Value (Margin of Safety = 100%)

In plain English, the model estimates that Hikma’s dividend will grow by about 8% per year for the next decade and by about 4% per year after that. This means the dividend is assumed to approximately double over the next ten years, which I think is a realistic and conservative assumption. Also, my target buy price is £9.87 and my target sell price is £20.31.

V.4. Is there a sufficient margin of safety between price and fair price?

NO: When I added Hikma to my portfolio in October 2022, its share price was £13.20 and although that was above my target purchase price, it was fairly close. At the time, I wanted to add another defensive stock to the portfolio and Hikma looked like a high-quality defensive stock trading at a fairly attractive price.

In terms of dividend yield, Hikma’s yield in October stood at 3.6%, which is slightly below my preferred yield of 5%. However, I was okay with that because Hikma is a relatively high-growth business, so I expected higher dividend growth to more than offset the lower dividend yield.

Fast forward seven months to the beginning of May 2023 and Hikma’s share price has increased to £18.51. That is now much closer to Fair Value than Good Value, as shown by the Margin of Safety, which has fallen to just 17%. That puts Hikma into my “sell zone”:

- Rule of thumb: Consider selling holdings where the Margin of Safety is below 33%

- Rule of thumb: Consider buying stocks where the Margin of Safety is above 66%

Hikma’s rising share price has also pushed its dividend yield down to 2.4%, which is starting to look very anaemic next to my target yield of 5%.

There are other holdings in my portfolio with far higher dividend yields and far more attractive valuations, so it makes sense to sell Hikma and reinvest the proceeds into some those more attractive alternatives, and that is exactly what I’ve done.

The green and red boxes in the chart above denote buy and sell trades. I bought Hikma at an average price of £13.20 and sold on May 3rd for £18.51 per share. The net result is a capital gain of 40% and an abnormally high annualised total return of 86%, which of course is almost entirely down to luck.

In some ways, I’m disappointed because I like Hikma and would have enjoyed following its progress over many years, but I also want to beat the FTSE All-Share in terms of income and capital growth, so if it makes economic sense to sell up and reinvest elsewhere, that’s what I’ll do.

I have reinvested the proceeds from Hikma into another holding, which is a world-leader in high performance plastics, with a forecast dividend yield (including special dividends) of more than 5%, compared to Hikma’s yield of 2.4%.

As for reinvesting in Hikma, I would happily reinvest at anything below my target buy price of £9.87, as long as there were no alternatives that were even more attractive.

And if I had cash sitting around and nowhere better to invest it, I might invest in Hikma as long as its Margin of Safety was above 66%, which equates to a share price of £13.50.

Original Post

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source