Three female doctors sue L.A. County, alleging it ignored complaints about an abusive boss at Harbor-UCLA hospital

Three leading female physicians at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California, filed suit last week against Los Angeles County, the overseer of the giant teaching hospital, contending that its management ignored years of complaints alleging sexual harassment, retaliation and discriminatory behavior by Dr. Louis Kwong, who until recently was the head of the facility’s orthopedics department.

Dr. Louis Kwong.Harbor-UCLA Medical Center

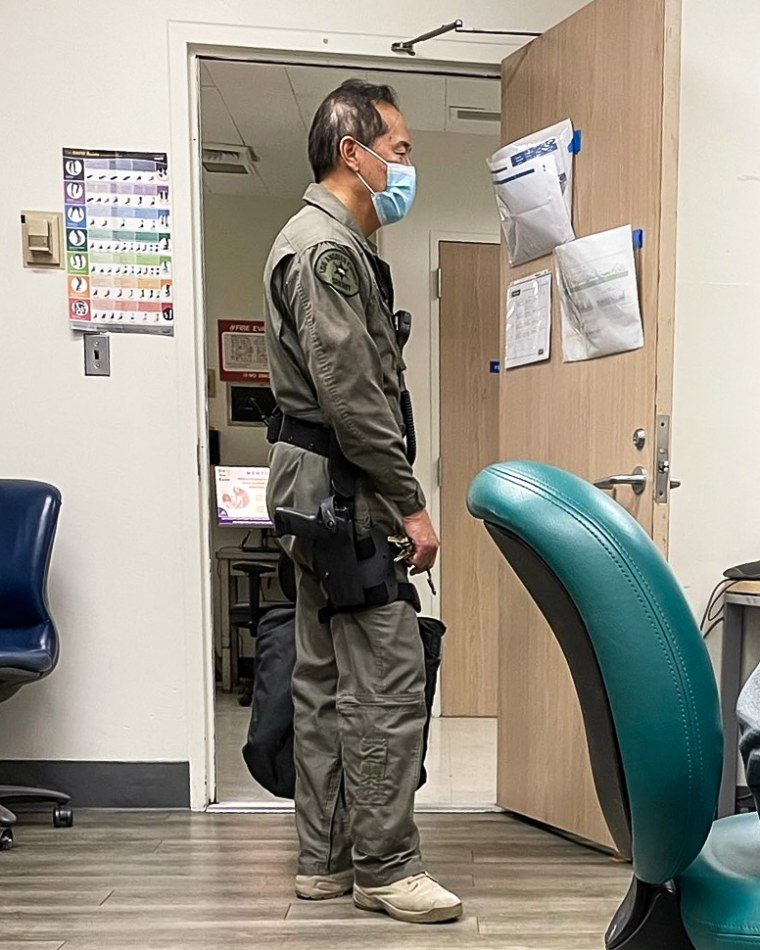

Kwong’s activities created a toxic work environment and put patients at risk, the physicians said in their suits, contending in one that he committed sexual misconduct on unconscious patients in the operating room, delayed acute surgery for county residents to perform elective procedures and once demanded that an operating room television on which a patient’s operation was being monitored be switched to a baseball game he wanted to watch during the operation. They say he also wore a gun at the hospital, including in the operating room; Kwong is a volunteer deputy sheriff in Los Angeles County, the county confirmed.

Misogyny permeated the facility, according to the suits. One doctor said she was asked to step down from her position to make way for a younger, less experienced male applicant. The department needed to give “a talented guy a chance before you turn into a pumpkin,” her lawsuit says she was told.

Dr. Louis Kwong with a gun at the hospital. He is a volunteer deputy sheriff for Los Angeles County.Obtained by NBC News

Dr. Louis Kwong with a gun at the hospital. He is a volunteer deputy sheriff for Los Angeles County.Obtained by NBC News

The plaintiffs are Drs. Haleh Badkoobehi and Jennifer Hsu — who are orthopedic surgeons — and Dr. Madonna Fernandez-Frackelton, a former longtime program director of emergency medicine at the facility. In their lawsuits, they say that they were demoted or otherwise retaliated against when they complained about Kwong’s behavior and that hospital administrators ignored written and verbal complaints about him for years.

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center is a level 1 trauma center in Torrance with 576 beds that serves a largely middle- and lower-income population. Los Angeles County’s Department of Health Services operates the hospital, which has a highly ranked residency program affiliated with UCLA Medical School.

The lawsuits involving Harbor-UCLA Medical Center follow other incidents at health care facilities affiliated with prestigious universities where complaints about doctors were allegedly dismissed for years.

Before they sued, all three physicians tried other remedies over many years, according to their suits, including filing grievances with the county and complaining to superiors. They say that the problems persist and in one of the actions say that they are suing to “help create a safer and more tolerant atmosphere” at the facility “for future patients, women and other targeted groups.”

“They rely on us being too ashamed and terrified for our careers to come forward,” Badkoobehi said in an interview.

Kwong was placed on administrative leave in March 2022, and the county hired a law firm, Sheppard Mullin, to investigate the allegations. The investigator at the law firm declined to comment.

While the investigation is ongoing and Kwong is on leave, he has earned as much as $1 million in pay and benefits in a year, according to the website of Transparent California, a public employees pay and pension database. A graduate of UCLA Medical School, Kwong has worked at Harbor-UCLA since 1990, his résumé shows. He did not respond to an email and a voicemail seeking comment.

In late June, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, the independent organization overseeing accreditation of post-medical school residency and fellowship programs, placed Harbor-UCLA on probation, according to its website. The move followed a site visit in April by the organization after Fernandez-Frackelton and all 64 of her emergency department residents submitted a complaint to the overseer about the toxic work environment in the hospital’s orthopedics unit, previously led by Kwong.

After she complained to her superiors about the toxic environment her residents encountered in the orthopedics unit, Fernandez-Frackelton, 53, was removed as program director of the emergency department. She had led it for 12 years, but in June, a younger, less experienced man replaced her, according to her lawsuit. Fernandez-Frackelton was told the department needed to give “a talented guy a chance before you turn into a pumpkin,” the lawsuit says.

A representative of the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services declined to comment on the litigation but said in a statement, “Harbor-UCLA Medical Center is committed to the health and safety of our patients and staff. These allegations of misconduct are being thoroughly investigated and, if substantiated, will result in appropriate corrective actions. We deeply value the trust the public places in our dedicated medical and patient care teams. Safeguarding patient care is our highest priority.”

In another recent incident involving UCLA, James Heaps, a longtime gynecologist at UCLA’s student health center and Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, was sentenced in April to 11 years in prison for sexually abusing female patients for years. UCLA paid $700 million to settle hundreds of complaints from Heaps’ patients, some of whom said the university ignored their complaints.

In June, Robert Hadden, a longtime former OB-GYN at Columbia University in New York, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for molesting patients over decades. An additional 300 Hadden patients sued Columbia this month, saying it had covered up for him. And last year, the University of Michigan paid $490 million to more than 1,000 students who said they were abused by Robert Anderson, a sports doctor.

Carol Gillam represents the three physicians in their lawsuits against Los Angeles County. In a statement, she said: “This story is unfortunately an all too familiar one about powerful doctors at prestigious teaching hospitals abusing patients and flaunting their own privileges and connections to the men who are supposed to supervise, discipline and remove them.”

Among the incidents involving patient abuse at Harbor-UCLA, according to one of the lawsuits, is an episode when Badkoobehi saw Kwong “engaged in ‘finger banging’ of surgical hip wounds” on an unconscious patient while making sexual sounds and saying he was “finding the G-spot.” In another, Kwong allegedly undraped an anesthetized patient in front of Badkoobehi “to look at his penis after being told it was large.”

Hsu also alleges that Kwong regularly delayed urgent trauma operations so he could perform elective, nonacute operations. “There were definitely times where we had to move other multiple patients around to accommodate his elective cases,” Hsu said in an interview, adding that the delays could extend to more than a week. That was reported to management, but Kwong faced no repercussions, the suit says.

Badkoobehi provided texts to NBC News showing that in 2016 the hospital’s CEO confirmed that the allegations against Kwong were “very serious” and that the facility’s risk management unit was aware and involved. Nothing changed, the surgeon said. All three of the doctors say they received lower pay than their male counterparts at the facility.

The suits describe misogynistic incidents at the hospital; one example: When Kwong asked other Harbor-UCLA employees, “Who wants to take body shots off Dr. Badkoobehi?” Residents in the Harbor-UCLA program were also encouraged to attend strip clubs together, one lawsuit says, with a female resident saying “she was taken to the strip club from work without her consent.” At a lecture by Kwong that students and residents were required to attend, it says, Kwong asked Badkoobehi and other women there: “What sexual position causes a penile fracture?” He kept pushing for a response, the lawsuit says, until he got the answer: “reverse cowgirl.”

As director of the orthopedics residency program at the hospital, Kwong attended faculty meetings to select candidates. At one point, one lawsuit says, Kwong held up pictures of two Black male candidates, asking: “Do you want Brother X or Brother Y?”

Since 2016, Kwong has received over $800,000 in payments from medical device and pharmaceutical manufacturers, more than the mean payments received by other physicians in the specialty, according to records from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. He has also received $665,000 in associated research funding from pharmaceutical and medical device makers on a project for which he is a principal investigator.

“I love working with the patients,” Fernandez-Frackelton told NBC News. “It’s an underserved population, the working poor in Los Angeles, and really satisfying and rewarding to care for them. But our system should respond to complaints about the inadequate care they are getting.”

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source