What to know about the proposed Republican cuts to Medicaid

Disabled protesters removed from House committee hearing

Disabled demonstrators protesting a Republican proposal to cut benefits were forced to leave a House committee hearing and arrested.

WASHINGTON – House Republicans are proposing sweeping changes to the federal Medicaid program that would kick millions of beneficiaries off the health insurance program, which covers more than 71 million low-income Americans. The bill would introduce a raft of new rules and regulatory requirements for those seeking coverage.

Families of four making as little as $35,365 would see new costs for going to the doctor, some unemployed people would become ineligible for Medicaid, some seniors would lose access to long-term care coverage, and states would lose a portion of federal dollars that help them cover those just above the poverty line. The bill would also bar Medicaid from funding services at clinics that also perform abortions, such as Planned Parenthood.

The proposal is part of a massive policy package that aims to implement President Donald Trump’s campaign promises, including an array of tax cuts that will cost an estimated $4 trillion over the next 10 years.

Under pressure from ultraconservatives in the Republican conference, congressional leaders are trying to find ways to offset that revenue loss with commensurate cuts to federal spending.

Health insurance benefit programs are one of the largest federal spending categories. Trump has said Medicare cuts are off the table, so changes to Medicaid became a central focus of potential cost savings for Republicans.

One in five Americans are on Medicaid nationwide, including around 40% of all children.

While the lawmakers did not include some of the more draconian cuts to Medicaid they had considered, the proposed changes are significant.

They would save the federal government at least $625 billion and cause 7.6 million Americans to lose their health insurance over the next 10 years, according to initial estimates by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. However, the impacts are likely greater, as the agency was unable to analyze the effects of at least 10 provisions in the bill by the time the estimates were released.

The CBO also estimates 1.3 million people who are both on Medicaid and Medicare, which provides health care for seniors, would lose Medicaid coverage. That means some benefits that Medicaid covers but Medicare does not, such as long-term care, would be lost.

“Medicaid is absolutely critical for children, for families, for people with disabilities and seniors,” said Joan Alker, executive director of the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University. “There’s a great deal at stake here.”

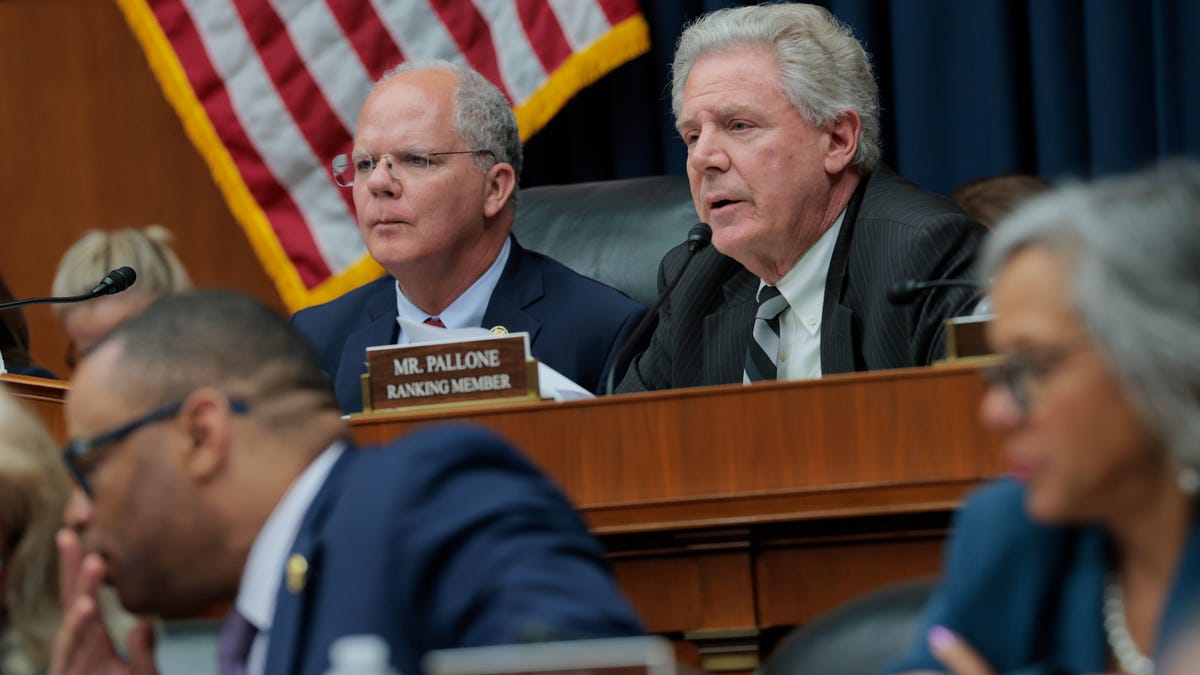

Both Republicans and Democrats alleged the other side was lying about its impacts during a tense House committee hearing May 13 to debate the proposal. Republicans argued the changes are intended to eliminate “waste, fraud and abuse” from the program and said it would not hurt the people who most need Medicaid, while Democrats argued the proposal would dramatically reduce access to essential healthcare.

“Medicaid was created to provide health care for Americans who otherwise could not support themselves, but Democrats expanded the program far beyond this core mission,” said Rep. Brett Guthrie, R-Kentucky, chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee that has spearheaded the Medicaid portion of the legislation.

“We are cutting money and health care from people and families who are suffering to pay for tax cuts for the rich,” said Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, D-New York.

So what’s really in the legislation? Here’s what you need to know.

Changes to Medicaid expansion

Medicaid was originally designed to provide health coverage for low-income Americans. The Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, expanded Medicaid to cover low-income adults who are not seniors in every state and made people eligible if they were making up to 138% of the federal poverty level.

That law also said the federal government would pay for 90% of the cost of the expansion, with the other 10% made up by states.

But states needed to adopt the expansion in order for it to be offered to their residents. Another law passed under former President Joe Biden created a financial incentive for states to do so.

This bill would eliminate that incentive. Right now, 41 states and Washington, DC, have adopted the Medicaid expansion.

The bill would also allow states to charge up to $35 per service for these adults covered under Medicaid expansion who make between 110% and 138% of the federal poverty level, which is currently $35,365 to $44,367 annually for a family of four.

Work requirements

The biggest change under the proposed bill would be the implementation of work requirements for adults enrolled in Medicaid expansion.

“Large shares – almost half of the (bill’s) estimated savings – are coming from provisions to require states to impose work requirements,” said Robin Rudowitz, vice president at the nonpartisan health policy organization KFF. “We know from other analyses and earlier estimates of these provisions that they do result in significant coverage loss.”

Even people who have jobs or are disabled can lose coverage if they don’t clear the bureaucratic hurdles. For example, a Medicaid work requirement program in Arkansas resulted in around 25% of those subject to the requirement losing coverage, primarily because they failed to regularly report work status or prove their eligibility for an exemption. Guthrie said during the committee debate that Republicans are not trying to model Arkansas, listing a the bill’s multiple exemptions.

Under the proposed legislation, people ages 19 to 64 would be required to show that they are working, doing community service or participating in an educational program for at least 80 hours a month. Some adults – such as pregnant women, people with disabilities, and people who are caregivers of dependent children – would be exempt.

It would also explicitly prevent the policy from being waived for certain states.

These changes would only go into effect in January 2029, after Trump’s term is over, though GOP hardliners are pushing leadership for those to go into effect sooner.

Increased eligibility checks

Right now, states are required to check whether Medicaid enrollees are still qualified for benefits once every year. The Republican proposal would increase the frequency of those checks to every six months.

States would also be required to proactively obtain updated contact information for Medicaid participants, including checking enrollee addresses to prevent enrollment in multiple states and regular review of the Master Death File to see if enrolled people have died.

States are also required to provide Medicaid coverage for qualified medical expenses up to 90 days before someone applies for coverage. The bill would limit that retroactive coverage to just one month before a person applies.

Medicaid providers would also be checked every month to determine whether they are still eligible to provide services under the program and would also be checked against the Master Death File.

The bill also includes provisions aimed at reducing the price of prescription drugs by adding new requirements for pharmacy benefit managers to prevent them from overpricing medication.

Discouraging coverage for undocumented children

It is already illegal for undocumented immigrants to get federal Medicaid benefits. However, states are required to provide Medicaid coverage to otherwise qualified applicants for 90 days while their immigration status is being verified.

The proposed legislation would end the requirement for states to provide coverage during that 90-day period. States would still be allowed to do so if they choose, but the bill bars states from receiving matching funds during that period.

Fourteen states use their own funds to provide health coverage to undocumented children, and seven states do so for adults.

The bill would punish states for using their own money to provide those services by reducing the expansion match rate from 90% to 80%.

Planned Parenthood in the crosshairs

Medicaid recipients are currently allowed to get services from any qualified provider, including clinics like Planned Parenthood, though federal funds cannot be used to directly pay for abortions.

The bill would bar Medicaid from paying for services of any kind at nonprofits that are primarily engaged in family planning or reproductive health and provide abortions.

That could be a sizable blow to Planned Parenthood and the women it serves: Around one in 10 female Medicaid beneficiaries between the ages of 15 and 49 receive family planning services at Planned Parenthood, according to KFF.

In addition to abortions, Planned Parenthood clinics offer birth control, pregnancy testing, STD testing, and basic gynecological services.

Another provision in the bill would bar federal matching funds for “gender transition procedures” for Medicaid or CHIP enrollees under age 18, including puberty blockers, hormone treatment or surgery.

Financing restrictions

Right now, states are allowed to raise money to pay for their portion of Medicaid spending through local government, state government, and health care-related taxes known as “provider taxes.”

The proposed legislation would bar states from creating new provider taxes or increasing the rates of any existing taxes.

People who support limiting provider taxes argue they are used to artificially inflate the amount of money the federal government pays into the program. Experts say restricting provider taxes would likely force states to make difficult choices to make up additional costs.

“There are very big cuts to Medicaid here, and states will not have any good choices to make up these lost federal funds,” said Alker of Georgetown. “States have to either raise taxes, cut people off, or restrict access and benefits.”

No Byline Policy

Editorial Guidelines

Corrections Policy

Source